Curiosity, Ignorance, and How to Spot Pseudoscience

Published:

About 3.7 billions years ago, on a small blue planet orbiting a humble star in a moderately-sized galaxy, the conditions so happened to be right for prokaryotic bacterial life to emerge. Through all the ups and downs that planet earth has been through since then, life has not only managed to survive, but it has also evolved into more complex forms. Because the planet’s resources at any point in time are limited, species have had to compete both among themselves as well as with other species in order to survive. An ability to seek out information about the surroundings therefore proved advantageous, and it was rewarded through better access to food and shelter. Species that could do that better had a competitive advantage in surviving. Over millennia, therefore, through natural selection, life on earth has been hard-wired to be innately curious.

Curiosity may have come about as an evolutionary trait for life forms on earth to survive, but it has had immense consequences on the planet itself, perhaps most notably through one of the millions of species that this planet has birthed: homo sapiens. Humans are said to be the “smartest” species to have ever existed. Whatever one’s definition of smart might be, there is no question that the curiosity, intelligence and social nature of the human brain has made humans the most powerful beings on earth. (How we managed to do that while still freaking out at the sight of an approaching cockroach is beyond me.)

Our evolutionary colleagues in the wild (tigers, monkeys, deer, etc.) are content with gathering information about the nearest available prey or grass to feed on, while we seem to have developed an insatiable need for information of all kinds. In 2009, a study estimated that the average American consumes about 34 gigabytes of information in a single day. If our brains operated similar to wild animals, we would probably be content with information on where the nearest McDonald’s is. But our curiosity has led us to seek out more information and to ask more complex questions. Why does the earth revolve around the sun the way it does? How does the Universe work? What is our place in it? How did we come to exist? Is there a Creator? Philosophers and saints all across the globe have pondered upon these questions for many millennia. It is only now, however, that we are making some headway in answering at least some questions, largely thanks to the advent of science.

Admitting Ignorance

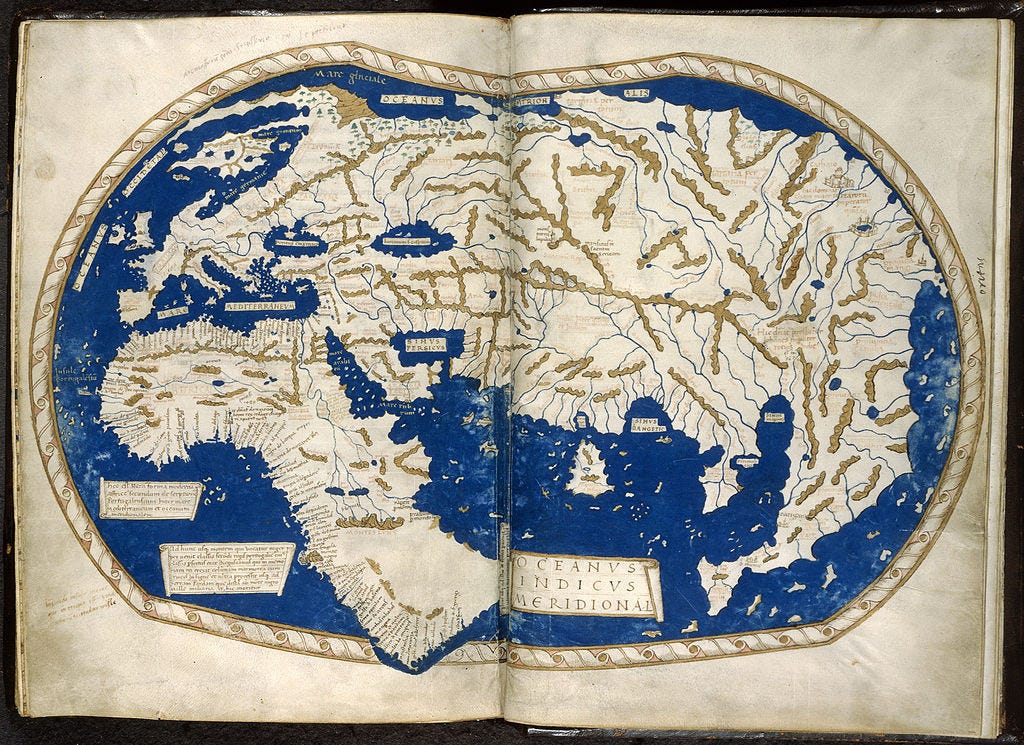

In late 1400s, Christopher Columbus set out to find a new route from Europe to China, India and the islands in Southeast Asia. At the time, Europeans were unaware of the existence of the Americas. Many medieval civilizations were convinced that they knew everything and that their maps of the world were complete. It was no wonder, then, that when Columbus sailed across the Atlantic Ocean and landed on the Caribbean islands in 1492, he had mistakenly assumed that he had found the East Indies islands. (Hence the misnomer ‘Indians’ for native Americans.)

7 years later, a little-known Italian sailor named Amerigo Vespucci had also set out on an expedition across the Atlantic. He too had found North America. Vespucci, unlike Columbus, was not set in blind belief of the old maps. He was convinced that the new lands that he and Columbus had found were not part of east Asia, but rather they were part of a continent that was unknown up until then. What followed is perhaps best quoted in the words of historian Yuval Noah Harari, from his book Sapiens:

In 1507, convinced by these arguments, a respected mapmaker named Martin Waldseemüller published an updated world map, the first to show the place where Europe’s westward-sailing fleets had landed as a separate continent. Having drawn it, Waldseemüller had to give it a name. Erroneously believing that Amerigo Vespucci had been the person who discovered it, Waldseemüller named the continent in his honour — America. The Waldseemüller map became very popular and was copied by many other cartographers, spreading the name he had given the new land. There is poetic justice in the fact that a quarter of the world, and two of its seven continents, are named after a little-known Italian whose sole claim to fame is that he had the courage to say, ‘We don’t know.’

The discovery of America was the foundational event of the Scientific Revolution. It not only taught Europeans to favour present observations over past traditions, but the desire to conquer America also obliged Europeans to search for new knowledge at breakneck speed. If they really wanted to control the vast new territories, they had to gather enormous amounts of new data about the geography, climate, flora, fauna, languages, cultures and history of the new continent. Christian Scriptures, old geography books and ancient oral traditions were of little help.

Henceforth not only European geographers, but European scholars in almost all other fields of knowledge began to draw maps with spaces left to fill in. They began to admit that their theories were not perfect and that there were important things that they did not know.

The idea of having incomplete knowledge was perhaps radical at the time, but as the subsequent centuries witnessed, Western civilizations embraced the idea that there is much more to be known about this world than was already known. This, of course, did not mean that it was all of a sudden acceptable to differ with the established knowledge base. In the 1600s, roughly a century-and-a-half after the “discovery” of America, when Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei proposed his heliocentric theory, the Catholic church was not happy. He was imprisoned, and eventually died while serving his sentence.

The Gift of Science

The arc of change and progress is said to be slow and cumbersome. Slowly but surely, contradicting with existing knowledge became allowed; even commonplace. A lack of hesitation in admitting ignorance, a penchant to seek out new information, and most of all a willingness to self-correct when presented with new evidence went on to form the fundamental tenets of the modern scientific method.

Needless to say, the success of the West in the scientific and technological advancements of the last few centuries cannot be explained with a simplistic view that admitting ignorance was sufficient. Scientific research at minimum requires resources, skilled individuals, and creativity enabled by free speech. One could make the argument that colonialism gave the West access to virtually unlimited resources, usually at the cost of other peoples. Furthermore, free speech, as we know today, is essential for unleashing individual creativity; the eventual democratization of Western countries, therefore, played a role too. All of these factors — and many more — are necessary, but no single one is sufficient by itself. Experience has taught us that in order to make true scientific (and I would add sociological and economic) progress, we must unlearn our made-up notions of knowing it all, and embrace the curiosity that evolution has equipped us with.

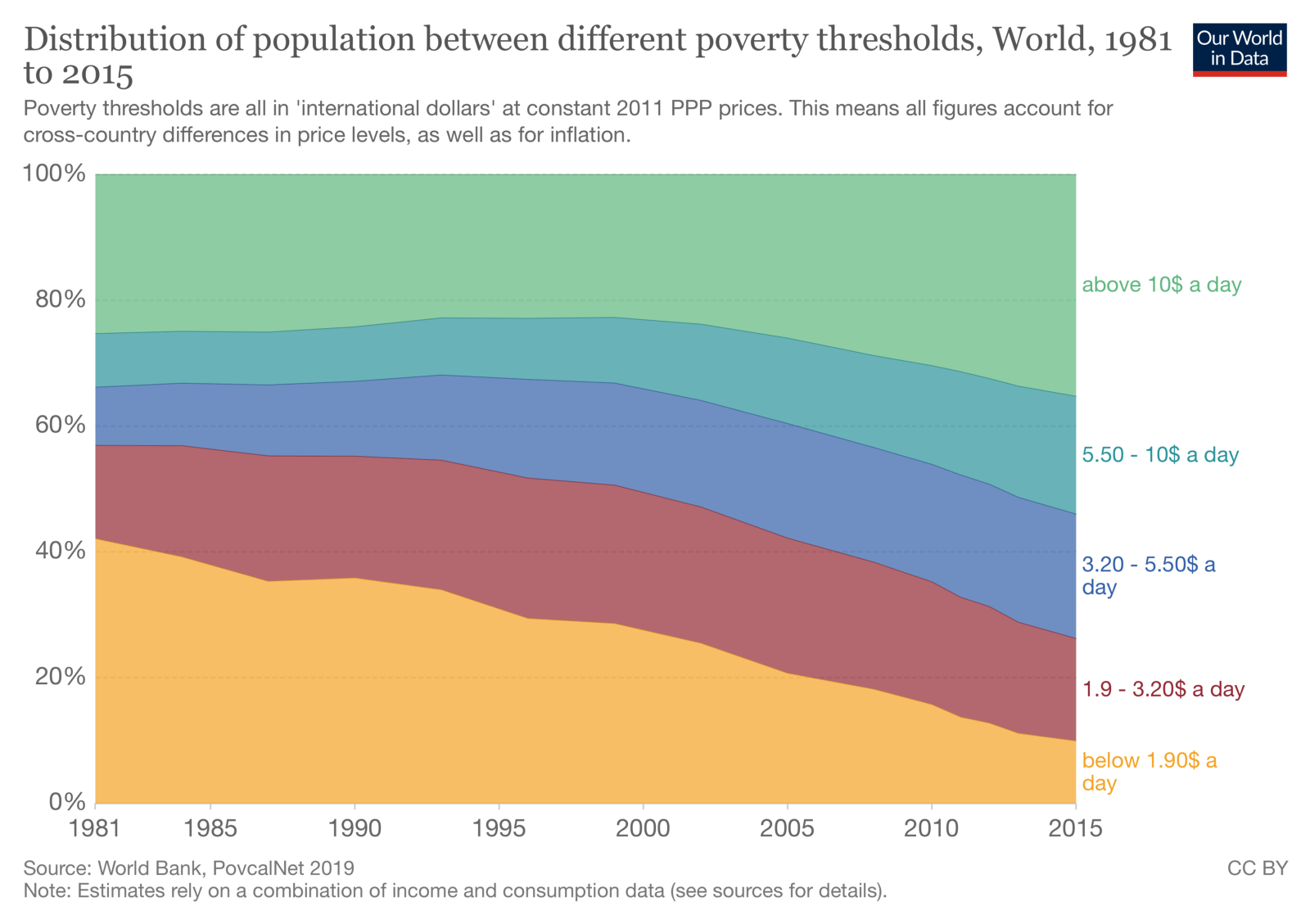

Over the last few centuries, science and technology have transformed our planet in enormous ways. Just in the last 100 years, the global average life expectancy has doubled. Numerous deadly diseases have been cured and vaccines have been developed. As healthcare improved and mortality fell, the population of the planet rose up faster over the last 100 years than it did at any time in history. Global poverty has dropped by over 30% in the last 30 years alone. (Some of this growth, of course, has come at a great cost to the environment. But that is a discussion for a different time.)

Rationality and Pseudoscience

If Galileo’s story shows anything about 17th century Italy, it is that the Catholic church of the time was capable of up-ending people’s lives for the simple act of observing nature and reporting findings. Our societies have certainly progressed since then, but this change has taken conscious and often painstaking effort. Just as the Catholic church saw Galileo’s findings as a threat to their power and influence, there are elements in our society today that see fact and reason as a threat to theirs. Today, while arresting someone — like Galileo was — for doing science is unheard of, there is a different — a more subtle yet potent—threat to science: pseudoscience.

Across the world today, we see countless instances of powerful forces pushing a pseudoscientific agenda for their own benefits. A prime example of this phenomenon is what some have called the “climate denial machine”. For decades, the fossil fuel industry has put in money and resources to deny science and shape public opinion on the state of the planet’s atmosphere to favor their profits. As the general public went about their daily lives unaware of the adverse impact that their modern lifestyles were having on the environment, greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere skyrocketed and the planet today is warming at an alarming rate. A similar story took place in the case of the cigarette industry: despite the adverse effects that research had pointed to, misinformation campaigns led by cigarette companies led to a growing number of lung cancer cases. In the US today, pseudoscience takes the form of anti-vaxxers and those that refuse to wear masks in the middle of a pandemic, the latter even being encouraged by politicians for political points.

In India, there is seemingly no dearth of ‘babas’ and ‘gurus’ promoting all sorts of pseudoscientific nonsense in the name of religion and spirituality. Jaggi Vasudev may have made use of the Indian obsession with speaking fluent English and to quickly become popular, but his quackery and irrationality are there for everyone to see. From ridiculing scientists after the discovery of the Higg’s Boson to dispensing “wisdom” on menstruation, there are countless examples of this man seemingly using “scientific” terms, but in fact spreading irrationality, all for profiting himself. (He is also known for his hypocrisy on various issues; my favorite instance is him calling protesting students out for not reading a bill that the government was trying to pass, while he himself had not read it and yet strongly supported it anyway.)

Temples, too, are known to use false science to reaffirm their legitimacy. Science may have doubled life expectancy in the last 100 years, but pseudoscientific treatments and cures to diseases and ailments continue to be troublingly popular. Homeopathy is a timeless example, but it looks tame when you consider the recent claim of a miracle cure to the coronavirus. Lately, there has also been a disturbingly strong push to promote the “healing properties” of cow urine, much to the chagrin of the country’s scientists who do the thankless work of doing real science.

Make no mistake, pseudoscience is not the same thing as ignorance. Christopher Columbus may have been ignorant, but his ignorance in itself was not a problem. The ignorance of the Catholic church about how the earth moves in outer space in itself was not a problem. Ignorance in itself is not always dangerous. What is dangerous, however, is a refusal to self-correct when presented with facts and evidence. What is even more dangerous is an insistence on an alternate reality that serves no real purpose but to benefit some: that is the very essence of the pseudoscience we are faced with today. Rationality threatens the power of some — and rightly so — while the pseudoscience that they propagate in return threatens the lives of us all.

How to Spot Pseudoscience

Galileo was alone in his battle for science, and not only himself but the entire world was worse off for it. Environmental protection agencies and conservation groups were alone in their fight against the fossil fuel industry until recently, and we have damning evidence today that we are all worse off for it. Collective activism is the only way to make long-lasting change in a democracy. Those of us that live in democracies, therefore, must make it a habit to use the free speech that our constitutions grant to us for this cause.

The scientific community will continue lead the fight against pseudoscience and propaganda, but we as a people will only succeed when all of us come together and do our part — scientists and non-scientists alike. We must work to establish a baseline of scientific temperament among the general public. An ability on the part of an average citizen to spot pseudoscience would be greatly helpful. To that end, here are some (not necessarily all-encompassing) tips on what to look for the next time you are presented with miracle “science” of temples or “logical” arguments for how vaccines cause autism.

1) Is it referenced?

This is perhaps the easiest thing to check. Does a written article on the magical powers of cow urine contain references to peer-reviewed research? When Jaggi Vasudev or Nithyananda uploads yet another video on social media and make claims of all sorts, do they seem to be referencing any sort of peer-reviewed research carried out at all? Does the politician reference a scientific journal article when he claims that climate change is a hoax? If the answer is no, you should be thinking “strike one”.

2) Is it peer-reviewed?

Even if someone claims to have come up with something so radically new that existing literature is not at all relevant, there are plenty of questions that need to be asked still. Before claiming of a miracle cure to a deadly disease, did they seem show any peer-reviewed evidence at all? Before making you pay your month’s earnings for a gem-stone that solves all of your life’s problem, did the astrologer seem to have performed peer-reviewed research? Or was he just trying to make money?

3) Straight to mainstream/social media

Another typical sign of pseudoscience is that they avoid the peer-reviewed journals (for obvious reasons) and instead go straight to mainstream and/or social media with their claim. A popular example of this is celebrities promoting unhealthy weight-loss products that have not been approved by doctors.

4) Citing anecdotal or ancient evidence

“Homeopathy works because it cured my aunt of high blood pressure.”

“Vaccines are harmful because that one guy (out of millions) had some side effects.”

“Indian traditions say that one shouldn’t eat food during an eclipse. Why, you ask? I don’t know why, but it’s a tradition that has been followed for thousands of years. All those people were not fools!”

They were probably not fools, but they were certainly ignorant of basic scientific facts. It is worth reiterating that the ignorance of ancient Indians in itself is neither surprising nor wrong. What is wrong, however, is blindly propagating what we now know for certain are unscientific. When you see someone doing this, it is worth taking a step back and asking some questions.

5) “They are suppressing us!”

If someone claims that they know the truth about something but the government or some advocacy group is suppressing their voice, that must be a red flag. (Galileo would perhaps have made this very claim, but that was in 17th century Italy when any disagreement whatsoever with the church would have meant trouble!) An example of this in physics is the free energy suppression conspiracy theory.

6) Nearly impossible to detect/verify

Despite how good smartphone cameras have gotten, is there ever a clear picture of the Loch Ness Monster or of a UFO? Conspiracy theorists often present “evidence” that is not convincing by any measure, but is branded as sufficient evidence nevertheless. When real scientists make measurements in the lab, there are very strict measures for what qualifies as evidence and what doesn’t. The “signal-to-noise ratio” of the claimed evidence is something worth paying attention to.

Final Thoughts

We live in strange times. Thanks to the internet and the ease of accessing it through smartphones and computers, it is easy to get information on just about anything. It is also equally, if not more, easy, to get misinformation on just about anything. Politicians, industries and godmen alike create their own alternative realities that they want you to subscribe to, and it has become impossible to establish a baseline of facts that all of us agree on despite all the access to information. To navigate these complex times, we must learn to trust our experts — scientists, doctors, economists — but we as individuals and as a people must also practice critical thinking. When the general public starts asking questions, most of the pseudoscientific claims quickly fizzle out. But when the public is successfully misled and confused, vested interests always win.

By construct, we are all born ignorant. We have, however, evolved to be curious. Nurturing that curiosity and being open to fact, reason and evidence can not only lead to healthier individual lives, but it can also benefit society at large. As a supporter of the idea of individualism, I am of the opinion that whatever you may choose to do for your own personal self — superstitions and irrational beliefs included — is only your business and no one else’s. But as a believer in our shared responsibility for looking out for one another — the idea of “citizenship” — I think that we must all make an effort to do the right thing for the sake of each other’s well being. In the context of science, that means that we support real science that has made the device you’re holding in your hand right now possible, as opposed to the forces that look to undermine it.

Life on earth has survived and evolved for long enough for us to be able to ask big questions. We are closer now than ever before to not only answering some of these questions but also in building a more rational and just society. In pursuit of such a reality, and in pursuit of saving a warming planet, it is not enough if some of us practice rationality while the rest of us continue to fuel charlatanry, misinformation and pseudoscience, for that only ever proves counterproductive. Promoting fact and reason is a collective responsibility of all of us. We can do better. And we must do better.

Suggested watching (also a reference for the tips listed here): “Thaumaturgy in the Age of Science” by Prof. V. Balakrishnan