Finding Meaning in Your PhD Struggles

Published:

The tattooing has taken only seconds, but Lale’s shock makes time stand still. He grasps his arm, staring at the number. How can someone do this to another human being? He wonders if for the rest of his life, be it short or long, he will be defined by this moment, this irregular number: 32407.

When he was 24 years old, in April 1942, Lale Sokolov was transported to the concentration camps at Auschwitz-Birkenau. He was only one of the thousands like him that were forcibly brought to these camps. Shortly after his arrival, he was put to work as the Tätowierer (tattooist) given his remarkable ability with languages: he could speak six languages. Lale was responsible for tattooing incoming Jews at his camp. During the years he spent at the concentration camp, he witnessed subjugation, torture, suffering, and death, but also incredible acts of bravery, courage, and compassion. In July 1942, he met a young woman named Gita who was trembling as she was waiting in line to get tattooed by Lale. On their first encounter, Lale sensed a connection with Gita. On that very day, he vowed to somehow survive the camp and go on to marry her.

In her bestselling book The Tattooist of Auschwitz, Heather Morris narrates the story of Lale and Gita in the concentration camp. It is a story of the horrors of the camps, but also of the bravery of the prisoners. It is a story of suffering, but also of optimism. It is a story of love, courage, and hope in the face of unfathomable circumstances. Lale and Gita not only survived the camp, but they also went on to live the rest of their lives together.

Needless to say, Ph.D. and graduate school struggles are not on the same scale as life in concentration camps; in fact for many of us, most of our life’s struggles aren’t. What is also true, however, is that the lessons learnt from survivors of camps are relevant to each and every one of us, no matter the magnitude of our individual and collective challenges. In his renowned book Man’s Search for Meaning, Austrian psychiatrist and camp survivor Viktor E. Frankl shares his groundbreaking insight into the mind of a camp prisoner. Drawing from his experience in the camp, he introduces to the reader concepts from the psychotherapy theory that he developed and pioneered: Logotherapy.

The lessons that I learnt from both of the books that I’ve mentioned here have been profoundly helpful for me during the incredibly challenging journey that my Ph.D. has been so far. In this article, I attempt to share some of these lessons, in hopes that a fellow Ph.D. student reading this might find it useful.

It really is hard

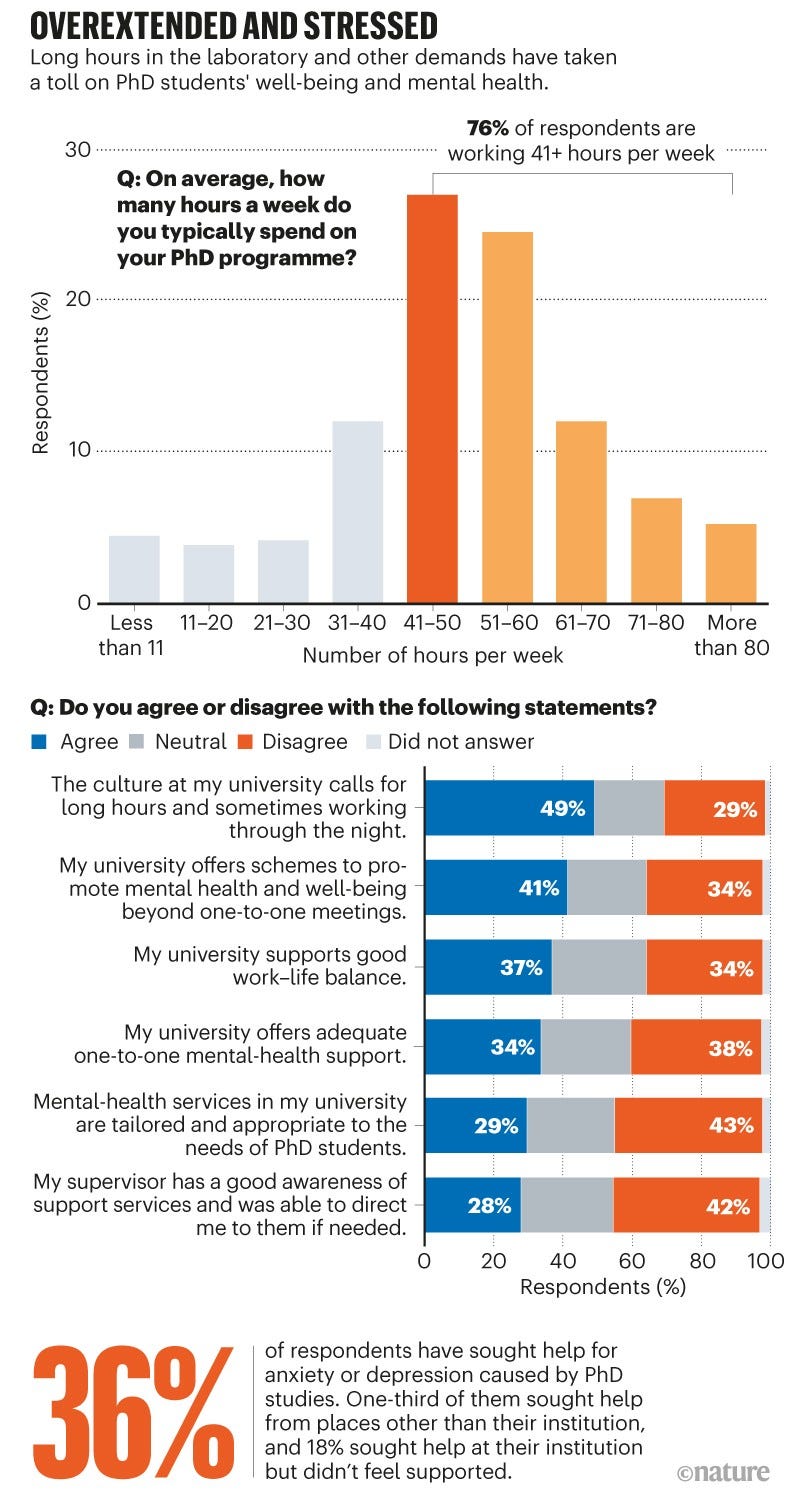

Last year, Nature conducted a survey of over 6000 Ph.D. students from diverse disciplines. The findings of the survey, though far from different from the findings of any such survey, were alarming: 36% of respondents have sought help for anxiety or depression caused by their Ph.D. study. This number, in fact, only seems to be growing. Many that suffer from anxiety and depression never seek help. The actual percentage is one that I do not even want to think about.

The underlying causes are many. It’s hard enough to get into graduate school: the application processes are too expensive for too many of us, and the average acceptance rates of 5–10% are not very encouraging. Systemic problems within academia of racial and gender discrimination, to this date, makes many feel alienated and out of place. Even if you were careful in choosing your advisor, you are likely to still have advisor issues. You might be putting in 70 hours per week of work, but you’re only paid for 20; and not even at an appropriate hourly rate. In an increasingly expensive world, this leads to financial stress among Ph.D. students. Isolation, anxiety, depression, and poor work-life balance are the lived experiences of far too many Ph.D. students today. Let’s not forget that the real job of these same students is one of the most challenging: doing novel scientific work and making a dent in the scientific knowledge base. The near 50% dropout rate in the US perhaps makes some sense. Whichever way you slice it, there’s no getting around the fact that PhDs these days come at a cost.

The potential solutions to these varied issues are equally varied. On a systemic level, work needs to be done not only in making women and racial minorities feel more welcome but also in bringing about more accountability in advising practices. Students shouldn’t be pressured into working for longer than a reasonable, mutually agreeable number of hours and hourly rates for a stipend must improve. On a more individual level, advisors must invest in their students’ learning and not force them to churn out publications for h-indices and citations. Universities must provide better-personalized care for the mental health of their graduate students, and awareness of these issues and potential measures must improve.

These ideas do not address all of the problems. Many of these ideas might, in fact, take years if not decades to come to fruition. And even if/when some of these problems are solved, challenges will still remain. At any given moment, an individual Ph.D. student can only do so much to help solve the larger issues and is usually left with having to deal with issues that are both in and out of their control.

This is not an article about solving the multitude of problems that graduate students face today. Rather, this is an article on how graduate students can rationalize some of the struggles that they face, find meaning in them, and hopefully better cope with the obstacle-filled marathon that the Ph.D. is.

Logotherapy

Logos is a Greek word that means ‘meaning’. Logotherapy focuses on the meaning of human existence as well as the search for one [wo]man’s search for such a meaning. Frankl states in his book that according to logotherapy, one can discover meaning in life three different ways:

By creating a work or doing a deed: In other words, by way of achievement or accomplishment.

By experiencing something or encountering someone: For instance, by experiencing goodness, beauty, nature, culture, etc., or by experiencing love.

By the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering: That is to say that even though one may suffer, it is still possible to find meaning in it.

While all of these ways are relevant in the context of a PhD, it is the last one that is least obvious. It is easy to see meaning in happiness. However, many of our cultures teach us to actively seek happiness and to avoid suffering, despite the fact that suffering at one point or another in life is inevitable. When we are faced with difficult times, therefore, we find ourselves wildly unprepared and overwhelmed.

It is one of the basic tenets of logotherapy that man’s main concern is not to gain pleasure or to avoid pain, but rather to see a meaning in his life. That is why man is even ready to suffer, on the condition, to be sure, that his suffering has a meaning. But let me make it perfectly clear that in no way is suffering necessary to find meaning. I only insist that meaning is possible even in spite of suffering — provided, certainly, that suffering is unavoidable. If it were avoidable, however, the meaningful thing to do would be to remove its cause. To suffer unnecessarily is masochistic rather than heroic.

The insight of logotherapy is fundamentally different from what we are taught in today’s world. Frankl says that finding meaning is what can lead to true bliss, and not chasing momentary happiness. In the context of Ph.D. struggles, understanding which parts are avoidable and which are unavoidable is the first step to finding meaning in them. Frankl says that it is possible to find meaning only in the unavoidable. Indeed, to suffer unnecessarily is not heroic.

Avoidable and unavoidable struggles

Frankl’s insistence on avoiding the avoidable makes intuitive sense: if you can save yourself from sources of anxiety, why would you not want to do that? In some life situations, it is easy to identify what is avoidable and what isn’t. For instance, in the case of toxic friends and relationships, the best way to deal with them is to avoid them. In the case of graduate school struggles, this distinction is not always easy to make, but possible nonetheless.

Financial stress, for instance, could be both avoidable as well as unavoidable. You could, in principle, cut down on eating and drinking out, live and eat cheap (although hopefully still eating healthy), avoid unnecessary expenditures, etc. At the same time, however, you alone might not be able to bring about a better hourly wage, control the cost of living expenses such as rent, utilities, and commute. In my case, while adopting a frugal lifestyle has helped some, I have realized that my university doesn’t pay me enough for me to have a safety net. One miscalculation and I find myself having to choose between paying rent and putting food on the table. Depending on your specific situation, you can assess to what degree financial stress is avoidable, and to what degree it is unavoidable.

Similarly, if you are facing workplace issues such as micro-aggressions, discriminatory treatment, etc., this can be addressed and “avoided” by reporting it to your advisor. On the other hand, whether or not the overall environment in your department or university is welcoming and inclusive enough is harder if not impossible for you to control.

If your work is anything like mine, you probably have to put in 60–70 hour work weeks more often than you would like. I have been able to “avoid” part of this by planning better and forcing myself to stop working beyond a certain number of hours even on busy days. The difficulty of the work itself and its often slow-moving pace, however, has been much harder to control. After all, if you are trying to push the limits of scientific knowledge, it should hardly be a surprise if it requires you to spend many back-breaking hours in the lab — even if things are breaking down half the time!

If your advisor seems to be prioritizing publishing and shooting for new grants over your learning, you could consider sitting down and talking with them. Ideally, that’s supposed to help — in which case you have avoided some suffering — but as most Ph.D. students would know, it does not always change much. Unless you are willing to switch advisors (which isn’t always practical) or drop out, this becomes an unavoidable struggle. If your advisor isn’t always able to give you the time that you’d like, having an honest conversation and making your expectations clear to them could sometimes help, but a lot of times it doesn’t, and you are left to having to deal with it.

I could go on, but you get the point: although it can be difficult to identify which parts of your struggles are avoidable and which aren’t, it is possible nevertheless. Being able to make this distinction is, in my view, the first step to being able to either avoid or find meaning in your suffering.

Finding meaning

Chances are that some (hopefully not many) of your struggles are unavoidable. Maybe you have a bad advisor situation and it’s not practical to switch advisors or do much else about it. If you’re like me, maybe despite your best efforts, financial stress is something that you’ve learnt to live with. Perhaps you already tried to socialize and find a company, but your work makes it impossible for you to make time for meaningful connections in your social life, leading to isolation; I have faced this too. Maybe you try your best to avoid stressors, but you can’t seem to fully control your worries or anxiety.

My advisor has fairly high standards for publishing papers. While competitor groups publish a new paper for every slightly new finding they make in the lab, my advisor insists on publishing only when we have something substantial to publish. To some degree, this is of course healthy. However, given the importance of publications in getting jobs these days, it’s hard for me to not be constantly worried about it. But soon enough, I came to realize that the mental battle that I somtimes have between worries about (not) publishing and scientific integrity was unavoidable.

For a good fraction of the challenges that I face, I have been able to find meaning. I often struggle to make timely progress with my research because of its complex nature and because I do it all alone, and it gives me anxiety almost every single day. However, I have been able to rationalize it to myself by recognizing that learning to handle complex projects by myself will only benefit me in the long run. Similarly, maybe my advisor has high standards for letting me publish a paper, but learning to adopt his level of scientific integrity will only make me a better researcher. His hectic schedule has some times meant that I figure things out by myself, but I have learnt to see things from his perspective and acknowledge that he always does his best to make time for me and that I must make do with what time of his that I have. After all, beyond a thing or two that I some times complain about, I am quite fortunate that I don’t have to deal with advisor issues that far too many of my peers deal with. Put simply, I have learnt to question whether my unavoidable struggles seem to either offer some value in the long run or serve a larger purpose.

It has taken me some time to internalize this way of thought toward my Ph.D. struggles, but I believe that I am better off for it. This is not to say that the struggles that I did and didn’t list here don’t bother me anymore; but rather, I am able to find purpose in them and accept them the way they are. In doing so, instead of running away from suffering, I have learnt to proactively embrace it. In doing so, I accept ownership of my situation — both the good and bad of it.

In some cases, I have found that there is perhaps no meaning to be found and that things on a larger scale must change. My university must pay better, they must have better mental health services in place, and they must work to make the graduate school experience easier for us Ph.D. students, not harder. As Frankl says in the excerpt above from his book, there is not necessarily meaning to be found in all suffering, but rather that it is possible — provided that it is unavoidable.

Suffering proudly

“[S]he who has a why can bear almost any how.” — Friedrich Nietzsche

Growing up, I saw my parents struggle through our financial difficulties. They put aside their comforts — sometimes even their basic needs — so that they could instead feed us or buy our school books. They sacrificed their dreams and they lived through all of the sufferings. How? They saw the meaning in their suffering: a chance for me and my sister to have a better life than they did. They found their ‘why’, and they lived through almost anyhow. They suffered proudly. Look around at the people in your life, and you will find many such examples too.

Although I have attempted to touch upon some of the common struggles that Ph.D. students face, the list here is far from exhaustive. Whatever your personal list may be, are you able to rationalize your unavoidable struggles and see meaning in them? It could be helpful to write down your struggles and complaints on a piece of paper and give yourself plenty of time to think about whether you are able to ascribe some meaning to your unavoidable suffering. You could even think about not just the individual struggles but the overall Ph.D. experience, and ask yourself if you have a ‘why’.

In my view, not everyone has a ‘why’, at the end of this process. For example, some fellow Ph.D. students that I know have it so bad with their advisors that it’s really hard for them to see meaning in their struggles and weigh it against what they might eventually gain from their Ph.D. In such cases, I believe that it is perhaps time to either have the department or the university step in or consider other alternatives such as switching advisors. For many, this can even end up being the reason for dropping out altogether, which is a shame, but also the unfortunate truth about PhDs these days.

Finding meaning, to me, is not only about being able to rationalize your unavoidable suffering and seeing past it but also about embracing it rather than running away from it. By changing my attitude toward my suffering, I have been able to take control and ownership of my situation, and I have been able to suffer proudly.

Final thoughts

The intent of this article is not to serve as “expert advice”. I am certainly not a psychotherapist. If you think you might need help, seeking help from an expert is always better than reading an article online, let alone one written by someone that’s not a therapist! This is especially true if you are about to take a major decision regarding your Ph.D. Seek advice from professional counselors and/or people in your life before making those decisions. If you are like me, however, and you don’t feel like you need help but you still have had trouble rationalizing your struggles and coping with them, I hope that you found this line of thinking useful.

There are certainly many systemic problems at various levels that need to be addressed in order to make graduate school a little easier on students’ mental health, perhaps especially in 2020. Even as we push to solve these issues, in my experience, I still have had to develop a perspective on my own Ph.D. life in order to be able to better deal with the challenges that it brought, regardless of whether these challenges were in or out of my control.

Reading Frankl’s book was highly instructive for me, and I recommend it to everyone. As I read Heather Morris’ book on the story of Lale and Gita, I could not help but notice that Lale is the very kind of man that Frankl says was likely to survive the concentration camp. Despite the enormity of the situation that he found himself in, his resolve and his hope never broke. Lale found meaning in his suffering. He discovered his ‘why’, and he lived through nearly 2.5 years of an awful ‘how’. Most of us are fortunate that our struggles are not as bad. But my hope is that whatever our struggles may be, we all find meaning in them and suffer proudly.

Suggested reading: Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor E. Frankl

This story was originally published by the author on Medium.